In 1840, the ambitious and then 26-year-old Belgian instrument maker Adolphe Sax developed a wind instrument that should incorporate all the good qualities of classical musical instruments. That first “saxophone” was a very large one, a bass saxophone with a very deep sound. After all, the longer the tube (and thus the larger the saxophone), the lower the sound. After Sax moved to Paris in 1842, he added smaller and smaller ones, with the sopranino being the very smallest.

From 6th to 14th of February 2021, it was very cold in the Netherlands. The surface water froze over even in Zeeland. In the little area called “Levensstrijd” near Zierikzee, a number of spoonbills were losing the battle for survival. Most were young, as young as six months old, but there was also an adult bird that did not make it. The winter victims were bitten out of the ice by Sven Prins and kept in a freezer until we got a better look at them.

With the (re)discovery of “ooking,” we had become curious about how spoonbills produce those sounds. Ooks are short soft sounds (it sounds a bit like “ook”) that spoonbills make before leaving a place in a group. So we were looking very closely at the sound-producing organ. In birds this is the “syrinx,” a small structure with two “eardrums” where the trachea splits in two, with short tubes to the left and right lungs.

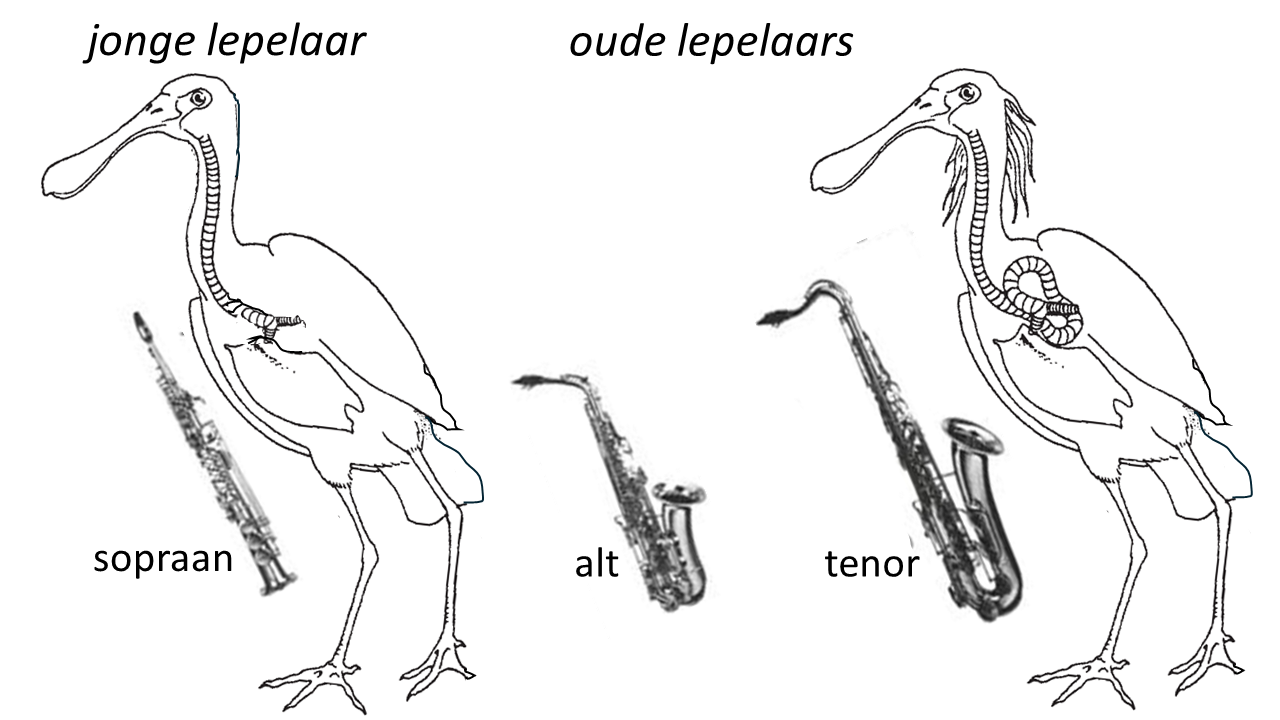

The young birds had a straight windpipe with a length of a good 20 centimeters. Exactly what you would expect. The surprise was therefore great when it turned out that the adult spoonbill had a windpipe with a curl, a large coil. That extension, folded as it were into the lower neck, made the trachea twice as long! Boy! That means that after everything about spoonbills is all grown out (bones, feathers, organs), the trachea apparently lengthens in the neck. And because the air blown through longer tubes leads to lower sounds, we suddenly understood why the ‘oek sounds of young spoonbills have higher frequencies than the ‘oeks of adult birds.

We thought we had made a great zoological discovery! That was a bit disappointing. When we searched the literature we found that the curled trachea of spoonbills had been known for a long time; it had been described more than 100 years ago by the industrious morphologists of the time. Nevertheless, it is spectacular that full-grown spoonbills, like humans, at some point “get the hang of it. As for their windpipe, spoonbills start with something that could be compared to a soprano saxophone. At some point, that windpipe grows into something resembling a tenor saxophone.

We have since been able to view more deceased spoonbills, including birds of known age from Artis in Amsterdam. It seems that males end up with a tenor saxophone (the adult Zealand winter victim was also a male), but females develop a windpipe that could best be compared to an alto saxophone.

Sketches of the straight trachea of young spoonbills, similar to a soprano saxophone, and the extended winding trachea of adult spoonbills. The latter could be compared to alto and tenor saxophones. - Source: adaptation of a drawing from Fitch, W.T. (1999) .

Sources:

https://www.bax-shop.nl/blog/muziekinstrumenten/saxofoon-geschiedenis-soorten-en-speeltechnieken/

Fitch, W.T. (1999) Acoustic exaggeration of size in birds via tracheal elongation: comparative and theoretical analyses. Journal of Zoology, London 248: 31-48.

Translated with DeepL.com