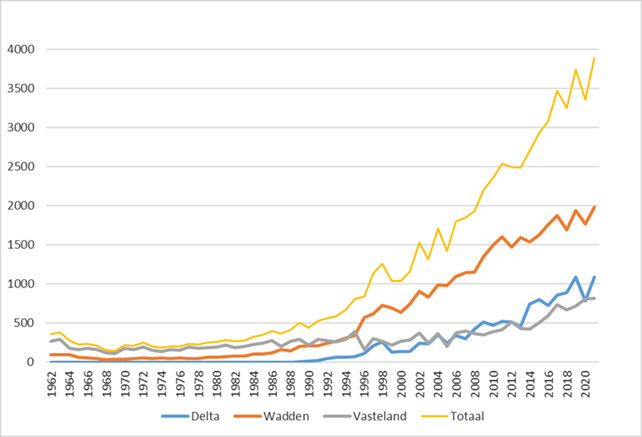

Mainly because of the use of pesticides in agriculture, the number of breeding pairs was historically low in the 60s and 70s. The number of breeding pairs has increased from 150 pairs in the late 1960s to more than 4000 breeding pairs in 2021. In the early 1990s, the population started to rapidly recover. From 1962 to 1979, there were only 6 large colonies in the entire country: Naardermeer, Zwanenwater, de Muy and de Geul (both on Texel), Terschelling and the Oostvaardersplassen. From 1979 onward, the number of colonies steadily increased. In 1997, there were already more than 20 colonies and in 2017 63 colonies.

The situation is now very different than about 30 years ago. In 1988, the famous spoonbill colony in the Naardermeer disappeared. In the same period, the spoonbills in the Zwanenwater and the Oostvaardersplassen started to have trouble with the increasing number of foxes that managed to reach and destroy the colonies in dry years. It seems that this triggered the spoonbills to search for other areas to breed, which they found on the Wadden Sea islands. In 1983, the spoonbills discovered the Schorren on Texel and Bomenland on Vlieland and in 1992 Schiermonnikoog, In the meantime, in 1989, also the island in the Quackjeswater was colonized. These colonies are still present nowadays. Spoonbills thus found places where foxes can’t come.

Nowadays, spoonbills are breeding on all Wadden Sea islands, but have also (re)colonized the inland and the Delta. From The Netherlands, spoonbills have also started to disperse to the German and Danish Wadden Sea islands, and to Belgium, France and the UK.

Currently, 4.000 pairs breed in The Netherlands. Is that a lot? If you compare it with the number of breeding pairs of cormorants (20.000-25.000) it still seems a vulnerable number. Moreover, the 4.000 breeding pairs in the Netherlands encompasses more than half of the West-European breeding population. Spain holds the second largest breeding population, but in years of drought, which have become increasingly common, hardly any spoonbills breed in Coto Doñana, which makes the contribution of the Dutch population even more larger.

Research on the Wadden islands revealed that the breeding success (the number of fledged young per breeding pair) of spoonbills decreased with increasing colony size. In recent years, spoonbills on the Wadden islands often raise less than one chick per breeding pair. Elsewhere, spoonbills have been shown to raise 2 or 3 chicks. This suggests that food availability is currently a limiting factor in the Wadden Sea.