As part of the project Waakvogels, 27 juvenile and 7 adult spoonbills in have been equipped with a GPS-tracker during the past breeding season in different Wadden Sea colonies. In addition, in collaboration with Lowland Ecology Network, two adult spoonbills were GPS-tagged in the colony at the Bataviahaven near Lelystad. The aim of the Waakvogels project is to better understand the importance of (different areas in) the Wadden Sea for six iconic migratory bird species, including the spoonbill.

In addition to this goal, the GPS-tagged spoonbills provide valuable information about the sites they use throughout the year, the routes that they travel to reach those sites, and also where, when and sometimes even why spoonbills die… This last bit is not the nicest aspect to be confronted with, but it does provide important information that can help us to better protect spoonbills in the future.

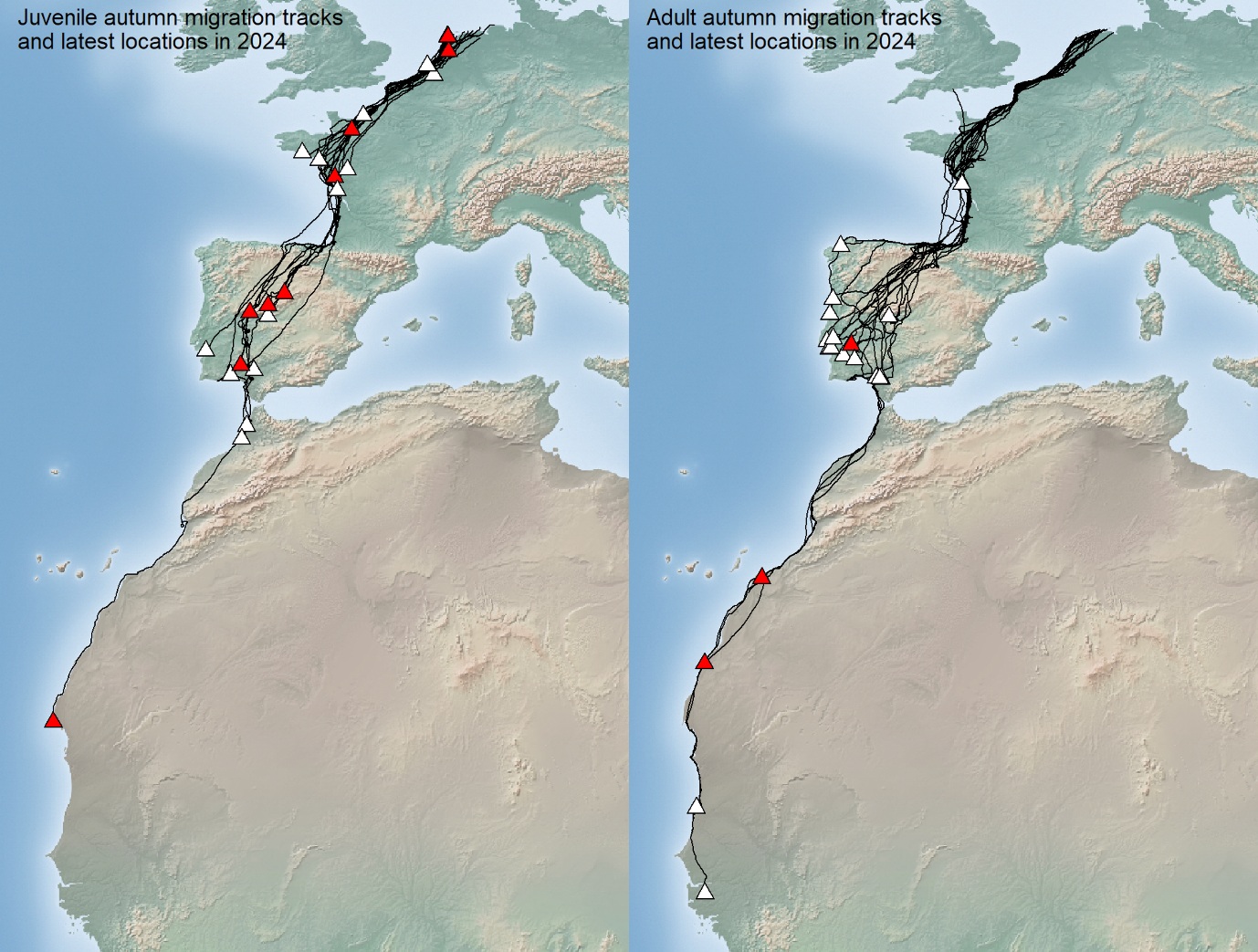

Below you fin dan overview of the autumn migration tracks of the juvenile and adult spoonbills. The triangles indicate where the birds are at this moment, and when they are red, it means that the bird died at this location. Of the 27 juvenile spoonbills that were equipped this year, 12 died so far. Of the 21 adult spoonbills that (still) had a working GPS-tracker in 2024, three died. Finally, there are 10 second-year birds with a still working GPS-tracker. They are all still in their non-breeding area since their first autumn migration, and they all survived the past half year.

Because the GPS-trackers send their newly collected data via the GSM network every 24 hours, we can very quickly determine whether a bird died. Subsequently, we try to mobilize our network of ‘spoonbill enthusiasts’ (e.g., bird watchers, ring readers and researchers) to search for the bird in order to hopefully assess its cause of death. In quite some cases this has worked out, and often surprisingly fast (for which we are very grateful!). Sometimes it doesn’t work, for example, when a scavenger finds the bird earlier and didn’t leave much behind, or because the bird died at an unreachable place. In those cases, it is sometimes possible through the combination of the locations of the bird prior to its death, the accelerometer data that gives an indication about the behaviour and angle of the bird, and satellite pictures on which suitable foraging habitats as well as power lines are visible, to still make a fairly reliable assessment of the cause of death. Below I give an overview of the individual mortality cases and their (likely) cause of death.

Of the juvenile spoonbills, five died while they were (still) in The Netherlands:

Carex († 16 June) died a week after he received his GPS-tracker, before he fledged. He was found and looked healthy from the outside. He was collected for further investigation. The same is true for Koen († 12 July) who died in a nature reserve in Drenthe.

The cause of death of Dirk († 19 September) is all the clearer. He crashed against a powerline near Ilpendam. A colleague found him with two broken legs. On the below photo it is clearly visible what Femke wrote earlier about collisions with powerlines, namely that the top two lines are hardly visible.

Dirk dies because of collision with a high voltage cable near Ilpendam. - Photo: Maarten Hotting

On 9 and 17 October, two juveniles (Zeno and Fuji) died along the coast of Texel. Based on the movements and data of the accelerometer, it appears that both birds were foraging while they ‘suddenly’ collapsed and were taken by the upcoming tide. Hardly anything was left of them when they were washed ashore at Den Helder and Vlieland.

Mortality during autumn migration

Waldi († 16 September) died suddenly while crossing the Iberian Peninsula and crashed in a copper mine. Whether it was a coincidence that it crashed exactly here we will never know, as we did not manage to reach the bird.

The place where Waldi crashed.

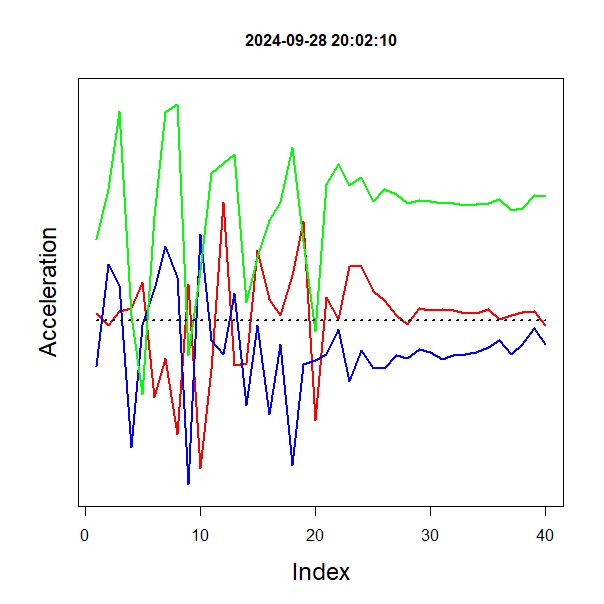

Vlieland († 28 September) departed in the morning from Zeeland and flew in the direction of Bretagne when she, being only several tens of kilometres away from suitable spoonbill habitats such as Ile de Ré, flew very low while crossing a railway line and landed in a pond just behind. It is unclear whether she collided with the electric wire of the railway line that ran right next to the pond, and crashed in the pond, or whether she landed there because she was exhausted. The accelerometer data do however show that she died very shortly after landing. The accelerometer also recorded her exact moment of landing/crashing:

Marjan († 4 October) has probably been caught by a golden eagle. She crashed while crossing the Iberian peninsula, and was displaced directly afterwards, presumably by a golden eagle, as the area is known to be a golden eagle territory. Spanish colleagues found the GPS-tracker a day later but no trace of Marjan.

Zwaluw († 11 October) was flying above a forested area in Northern France when she was ‘suddenly’ dead at a location off her flight direction. We therefore suspect that she was caught by an eagle owl.

Malgum († 24 October) stranded in the interior of Spain and seems to have been searching for food in vain. He presumably died from starvation.

Valerie († 7 November) was performing a seemingly very “grown-up” autumn migration, stopping for considerable amounts of time at places used by many other spoonbills. After a long stop in Doñana, she decided to continue migrating to Africa. After a few short stops along the Atlantic coast, she arrived on 5 November in Nouadhibou, where she after having foraged in suitable spoonbill habitat, appears to have crashed into a powerline.

Festuca († 6 December) already arrived in the interior of Spain in the beginning of October where she subsequently stayed. The sites that she used were probably not very suitable (at least not well known) and therefore likely died because of starvation.

Besides these young spoonbills, also three adults died:

After Dirk and Valerie, also Marie, an adult female that has been breeding (at least) in the past two years on Texel (she was ringed and GPS-tagged in 2023), flew into a powerline at night while migrating south along the coast of Morocco († 26 October).

Recently, also spoonbill Jan passed away in Africa († 26 November). He already reached the Western Sahara. On 18 November he stopped at an unknown site, Hassi Amatal, where he stayed until 22 November. Afterwards, he returned northward, back to Dakhla where had come from a few days before. While doing so, he made many stops to (apparently) rest, often in the middle of the desert. He seems exhausted or ill. Sometimes he shortly reaches the coast and forages for a while, and then continues flying north. Four days after his departure from Hassi Amatal, he passes away, presumably due to starvation.

At the day of writing, the sad news reaches me that also Batavia has passed away († Friday the 13th of December). She shuttled back and forth between insiginificant sites in southern Portugal. Sites that may have contained enough water and food to spend the winter in previous years, but not this year. Or perhaps she was on her way to the coast of Portugal (e.g. Tagus estuary), but her reserves ran out too soon, and she tried to refuel in these unsuitable sites. She presumable died of starvation.

Summary

If we assume that the birds of which we could not find out the cause of death died because of starvation or exhaustion, and that our suspected causes of death are correct, then 11 birds died due to ‘natural’ causes (exhaustion, starvation or predation) and 4 due to human actions, in all cases due to collisions with powerlines. Of these four cases, two are certain (Dirk and Marie) and two probable (Vlieland and Valerie). If these numbers are representative for the entire population, then this would mean that in half a year time 4/(27+21) = 8% of the population dies due to collision with powerlines. Of course, the sample size is too small to make such generalisations, but that powerlines form a serious threat to spoonbills may be clear. Because of these mortality cases, as well as mortality among untagged birds over the past years, Werkgroep Lepelaar has raised the alarm about this. This resulted in a recent publication by Birdlife Netherlands where they plead for more and better measures against collisions with powerlines, which will not only save many spoonbills but also other bird species.

Over the past half year, the survival of the GPS-tagged birds was (27-12)/27 = 56% for young (first-year) spoonbills and (21-3)/21 = 86% for adult spoonbills. This is very comparable with the annual survival rates estimated from colour-ring data, being 56% for juvenile spoonbills and 88% for adults. However, only half a year has passed, and therefore, the eventual survival rates will probably be lower. However, it was previously shown that the majority of mortality among first-year birds took place between fledging and arrival in the wintering areas.

The ongoing adventures of the 15 juvenile, 10 second-year and 18 adult spoonbills that are still alive can be followed online via https://maps.nioz.nl/spoonbills-NL and the mobile app Animal Tracker . If you happen to encounter one of them in real-life, we would be very happy if you could send us information about the (apparent) condition of the bird and whether the bird is in good company (i.e. are there other spoonbills present, are these juvenile or adult, and are there any colour-ringed individuals among them?).